There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

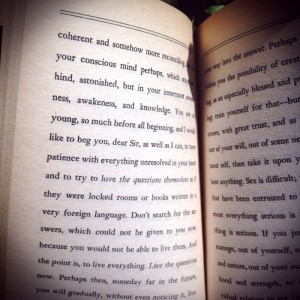

You are so young, so much before all beginning, and I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer. (Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. Stephen Mitchell)

So again, here’s patience—with the mystery of our most unresolved, anguished questions, those lodged in our hearts as if locked in rooms or as if lying just beyond our comprehension on the pages of a seemingly (very) untranslatable book. Clearly knowing the discomfort of holding those questions himself, the poet gently advises his young friend to try to love them. Not to love them, but to simply try. And then to wait, maybe for a really, really long time, for the answers to become visible, tangible, livable.

For Rilke, the waiting erupted into poetry.

One of the biggest challenges for me in my practice of yoga has been that, when it comes down to it, the learning‚ the discovery, and the baby-step-by-baby-step resolutions are all essentially and fundamentally experiential. For an ex-academic inclined to hoard reference materials and to do impressive amounts of research before embarking on just about anything, this is a huge deal.

And this is why Rilke’s advice moves me, and why it is so important for me. Every time I close my eyes before meditation practice or move into an asana or slow and deepen my breath in pranayama, I am struck (I swear it often feels physical) by how “so much before all beginning” I am, especially in the face of the enormity of my endeavor and its importance. The practice and the reason for the practice are everything, and it is often like stepping into darkness; I cannot see where I am going. How I respond is my choice: I can turn back, I can fume, I can give into doubt, uncertainty, or fear, or I can present my questioning self, do what I know, wait, and cultivate patience. It’s not easy; I am waiting to “come into” the answer of the meaning of my existence—or more accurately, I am waiting for the answer to come into me, living in the urgency of the question, trusting that the answer will come, probably piece by piece, when my practice has prepared me to live it. And I don’t know when this will be.

Yoga philosophy, of course, promises that each of us already has the answers and they comes to us from within. So perhaps I should say that I wait for the answers to emerge into my self-awareness, to crack that perspective open so that I live everything even more fully than with the questions alone, as more of who I truly am.

If all of this is too heady, or all of this stuff about patience and waiting and emerging self-awareness just too wearing, we can come back to the things that the practice gives us as we do it. When it comes to meditation, the ongoing fruits are something like these (in the words of a master yogi and teacher):

Meditation will give you a tranquil mind. Meditation will give you awareness of the reality deep within. Meditation will make you fearless; meditation will make you calm; meditation will make you gentle; meditation will make you loving; meditation will give you freedom from fear; meditation will lead you to the state of inner joy called samadhi. These are the results of meditation. If you understand these goals and want to meditate, then it will help you… (Swami Rama, The Art of Joyful Living)

Rilke says in yet another letter, “What is happening in your innermost self is worthy of your entire love.” All the practice, the sitting with the questions, the trying to love them, the failing or the not failing . . . all of it is worthy of our deepest devotion—every drop of it. For each of us is, after all, so worth being, and so worth waiting for.